I last wrote about What’s Going On?, the album, just over fifteen years ago and began my piece with the same Beckett analogy is not out of place with Marvin Gaye. I think that we still need to be clear about a key point – What’s Going On?, the album, or extended twelve-inch mix, is not Noam Chomsky set to music, is not an exhaustive yet pertinent blueprint for a perfect society, is not an orchestrated adaptation of Socialist Worker editorials, sets no agenda, does not pretend to speak for anyone except the man who was responsible for it, and – crucially – those who cannot speak for themselves. It is routinely voted into all-time top ten album lists, I suspect by people who do not really know what’s going on with the record – and I note that the record’s critical recognition did not really come about until after Gaye’s death. It is an intricate (more often than not painfully intricate) examination of the assumed disintegration and disordering of a man’s mind.

In many ways What’s

Going On? was, implicitly and explicitly, an anti-Motown record; explicitly

because Gaye wanted to do things his way, wanted the title song – conceived and

recorded before the notion of an album had even been considered - released as a

single and refused to record or release anything else until Berry Gordy wearily

agreed. Why introduce reality into the fluffy kitten of a world that was Motown

in 1970? We’ve got along fine doing it our way…don’t spoil our fun (or, more

importantly, our profits). Moreover, don’t take us back – listening to the

multidirectional scatting on the song, Gordy sighed that this was old Dizzy

Gillespie shit. However, “What’s Going On?,” the song, demonstrates that Gaye

knew exactly what he wanted.

The initial idea for the song came about when the Four Tops

singer Renaldo “Obie” Benson was on a bus and witnessed police beating on

protestors in the People’s Park, Berkeley. Disgusted, he came up with the

embryonic song on guitar and took it to Motown staff writer Al Cleveland.

Eventually they offered the song to Gaye – initially, Gaye felt it would be a

good song for the vocal group The Originals (whom he was producing at the time)

but Benson and Cleveland convinced him to record the song himself. Gaye

reworked it to a quite drastic extent, recorded the song and Gordy blanched.

However, others at Motown managed to sneak out 200,000 singles of the song for

distribution in early 1971, and when it turned out to be Motown’s

fastest-selling single to date, Gordy conceded and requested that he record an

album around the concept of the song. This Gaye did over the first ten days of March

1971 with most of the Motown regulars on hand, including strings arranged by

David Van DePitte (credited the “Fastest Pen Alive” on the sleeve) and major

musical and lyrical input from Benson.

There are also personal reasons why What’s Going On? might be considered anti-Motown; Tammi Terrell,

Gaye’s preferred female singing partner, had died in 1970 of a brain tumour,

having collapsed in Gaye’s arms onstage some months previously. It was said

that the onset of her tumour was a direct result of an injury sustained to her

head by her then partner, ex-Temptation David Ruffin, at the time still the

epitome of full-on “maleness” in Motown music. So it was made in the light of

bereavement, both personal (Terrell) and symbolic – his younger brother Frankie

was away fighting in Vietnam. Moreover, Gaye himself was in the middle of a

cocaine habit, was in trouble with the IRS and even considered quitting the music

business and trying out as a football player with the Detroit Lions (hence the

appearance of some of the latter on the title song). And there was always, always, the folk memory of the Watts and Detroit riots.

The first thing we have to consider about What’s Going On? is the duality

expressed by the presence of the two saxophone soloists, Eli Fountain on alto,

and Wild Bill Moore on tenor. Both were given the master tapes and asked more

or less to solo throughout all the tracks; their contributions were then edited

and faded into the foreground when aesthetically required. Fountain represents

the female or “mother” side of Gaye’s personality, his graceful, kind and warm

tone very reminiscent of the then recently deceased Johnny Hodges (and his

playing is significantly predominantly featured); while Moore’s tenor is the

male and (sinisterly?) the “father/he-man” side of Gaye, hard-toned and

thrusting forwards, explicitly under direction to do a Pharaoh Sanders or

Archie Shepp – indeed, both Sanders and Shepp were approached to solo on the

album, but were contractually bound to ABC/Impulse Records at the time (this in

itself lends an interesting perspective to Shepp’s curious near-miss of an

album, 1972’s Attica Blues, which

quite openly is his attempt to do a What’s

Going On?). Moore’s playing suddenly comes into the spotlight when a

particularly emphatic point (or anger) has to be made (or expressed).

The utopia to which seventies soul music repeatedly returns

was primarily constructed out of the title track of What’s Going On? As mixed and heard on the album, Gaye parties with

members of the local football team (stoned or not stoned?) in the background,

while the (apparently accidental) duality of his various vocals is made more

prominent – the voice singing, the mind thinking something else (James Jamerson

came into the studio drunk, and had to play his bass sitting on the floor –

still he knew enough to come home that night and tell his wife that he had just

played on a masterpiece). The duality comes back again and again throughout the

album. And there is never any “soul” singing as Brown or Pickett would have

recognised it – the approach of Gaye’s light tenor we now can appreciate more

fully in light of his expressed admiration for Jimmy Scott; and indeed it is

virtually asexual, as though he is looking down with great reproach at the

world to which he remains umbilically attached.

The album is essentially a half-hour extrapolation on the

title song. The same main musical motif introduces the second track (and the

rest of side one segues continuously) “What’s Happening Brother.” Constructed

as an imagined dialogue between Gaye and his Vietnam-based brother, the

viewpoint alternates freely between either; Gaye’s own personal day-to-day

agonies (“Can’t find no work, can’t find no job my friend”) set against

Frankie’s heartbreaking attempts to hang onto some sort of recognisable reality

(“Are they still gettin’ down where we used to go and dance/Will our ball club

win the pennant, do you think they have a chance?”). The climactic final lines

“What’s been shakin’ up and down the line/I want to know ‘cause I’m slightly

behind the time” could be said by either. At that point the music decelerates,

goes into momentary dissonance under Gaye’s anguished falsetto croon before

mutating into “Flyin’ High (In The Friendly Sky).” Here the “utopia” becomes a

woozy anaesthetic, James Jamerson’s inverted bassline (compare with John Cale

at the close of the Velvets’ “I’m Waiting For The Man”) commenting ironically

on Gaye’s mental destabilisation as he attempts to seek refuge in drugs, always

aware (“so stupid minded”) that there is “self-destruction in my hand” and that

he has become “hooked…to the boy who makes slaves out of men.” In the

background one of his alter egos muses “Nobody really understands.”

But he can’t destroy himself when others are set to be

destroyed through no fault of their own. So the music re-focuses into the

orchestra and chorus waltz of “Save The Children”* where Gaye’s song is echoed

deliberately by his far less certain spoken voice. Can he believe what he is

singing about the end of the world? The music stealthily builds in tension and

both Gaye’s singing and speaking voices rise – perhaps tearfully, perhaps

orgasmically. As both of their voices decide to “save the babies,” the pent-up

tension of the music suddenly breaks free into an ecstatic rhythmic 3/4 carousel over which Fountain’s alto floats in a heartbreakingly brief expression of

freedom. But Gaye the realist quickly stops it all with an extended “But…”

before the “What’s Going On?” music starts again and he modifies it into “But

who really cares?” He still has to care, so it’s a return to ecstasy for the

glorious “God Is Love” where for the first time on the record the music is in

an unambiguously major key, trumpets (of the Angel Gabriel?) joyfully blaring

as Gaye reasserts his own faith. The attendant irony of “love your father” is

of course only detectable retrospectively (and hear the whisper behind “Don’t

go and talk about my Father (i.e. God)” which warns “Don’t talk ‘bout spiritual

lust (i.e. his own father)”) but the grievous punctum comes when he reaches the

line “Love your brother” and his alter ego suddenly screams “MY BROTHER!” and

briefly overwhelms the entire track.

(*”Save The Children” was the only single from the album to

appear in the British charts at all during this period, largely because of

being played repeatedly by Tony Blackburn, who ignored Radio 1’s instructions

not to play anything from the record because it was, apparently, “too

depressing.” Even then, it only appeared for one solitary week at #41).

The vision is there, its articulation as yet incomplete. We

now move into the climax of side one, “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)” where Bob

Babbitt takes over from Jamerson on bass and a bewildered Gaye asks “Where did

all the blue skies go?” before musing on the “poison in the wind that blows

from the north and south and east.” Moore’s outraged tenor rips through the

musing for a moment or two, before the opening “What’s Going On?” motif yet

again returns and remains unresolved, culminating in what is still one of the

most frightening endings in all popular music – the sudden and completely

unexpected appearance of the Moog synthesiser, not quite for the first time on

a Motown record but certainly the most pronounced, as the song/sequence grinds

to a halt, giving way to the terrible horror of the closing inhuman “voice,”

Gaye’s piano issuing a repeated, crashing, dissonant toll as though he is

smashing his own right hand (and the “voice” emanates from Gaye’s own

Mellotron, although it is worth noting that around this time Gordy employed the

veteran Raymond Scott as an electronic music consultant – I am not clear what,

if any, input Scott may have had here). Another Dies Irae for the world’s end.

Side two is where Gaye tries to find some answers. “Right

On” begins as a typical early seventies soul-funk workout, very much in the

Isaac Hayes/Curtis Mayfield mode, Danya Hartwick’s flute well to the fore.

Eventually Gaye’s voice enters. He begins what you eventually realise is a

prayer of salvation, a list of those who will survive:

“For those of us who simply like to socialise.

For those of us who tend the sick…

For those of us who got drowned in the sea of happiness.

For the soul that takes pride in his God and himself and

everything else.”

Fountain’s mothering alto watches over him from above.

Because it is love that will save us. Yes it’s that simple, yes it’s that

unattainable. The tempo briefly quickens up as though love is to come (in

either sense), following which the music metamorphosises into Sinatra (with one

further blast from Moore’s tenor). Apostolic strings, Gaye’s voice pleading

just as it’s coming on: “PURE love can conquer hate every time” – he finds as

many variations on expressing the word “love” as Van Morrison did in “Madame

George” – and, inevitably, the need for personal love becomes evident and

finally predominant. Listen to him inviting you: “And my darling, one more

thing/If you let me, I will take you/To where Love is King/Ah, ah, baby” – the

final line is wept. PLEASE KEEP ME ALIVE is the subtext, while the

orchestration, assorted major and minor sevenths and Gaye’s own delivery lead

one to wonder whether Nat “King” Cole, Gaye’s great idol, might have attempted

something like this had he stayed alive.

The groove restarts, briefly, followed by percussion and

alto clip-clopping in unison, and then it is time for the epiphany – “Wholy

Holy” where Gaye now pleads for the entire world, all humanity, to become his

Other. “We can (and how close to “can’t” his voice seems to sound) conquer hate

forever…we can rock the world’s foundations” – if only you’ll let me. So

peaceful, yet so confident a prayer (the graceful if ever so slightly regretful

descending chords – proto-Badalamenti), he asks us to believe in Jesus and

almost uniquely in popular music you want to believe it too. He very nearly

persuades you.

Except of course that it’s a dream, a utopia, which cannot

yet – if ever – be converted into reality. And even Marvin Gaye has to wake up

to what is the most tangible and most perceptible “reality” – the world,

America, as it stood in 1971. “Inner City Blues” (a title thought up by Gaye

and co-writer James Nyx, Jr, the latter a janitor, lift attendant and

occasional staff songwriter at Motown) is where, having reminded us of how high

we could reach if we wished, we have to have our faces rubbed in how things

actually are. We have to confront the shit in which, if we look at the sky for

too long, we may end up buried. Another list, this time of things which will

kill; the inability to pay one’s taxes, the banality of one’s own “hang-ups,

let downs” set against moonshots (don’t be flying high, give your love and

money to the have-nots), capitalism (for years I thought he was singing

“Inflation, no chance/Too many creeps finance” though actually it’s “to

increase finance”), and finally (could it ever be firstly?) apocalypse (“Crime

is increasing/Trigger happy policing/Panic is spreading/God knows where we’re

heading”). Is my alternative really so woolly, he is asking. The music is low

cast, Babbitt’s bass flowing like cynical blood through the aorta of the

strings and the death march piano chords. The piano finally takes us back to a

reprise of the key lines from the song “What’s Going On?” to complete the

cycle:

“Mother, mother (my God, how he emphasises the “mother,” how

right it’s Eli Fountain’s alto which should take us out of the album)/Everybody

thinks we’re wrong/Who are they to judge us/Simply ‘cause we wear our hair

long?”

Sung by someone who would never be seen dead in long hair,

who appears on the sleeve wandering around a children’s playground in the rain,

dressed in a smart black raincoat, black suit and a wide gold tie, smiling

benignly.

And we do not quite return to a loop – just Gaye’s wordless

vocals, Fountain’s alto and percussion. God knows where they’re headed. Eventually

Gaye would move from his dissertation of big deaths into a microscopic examination

of the little death, but that isn’t what concerns me here.

Observations

1.

I note Dave Marsh’s comment that the title song – in

combination with the rest of the record – is the kind of music that could only

really have been made by close and trusting friends, sheltering from the horror

outside.

2.

The question about 1971 is not whether What’s Going On? is one of the greatest

albums ever made – it is – but

whether it was even the best album released in 1971 with the words “Going On”

or “Goin’ On” in its title. But Sly’s is a different, parallel story.

3.

That What’s Going

On? influenced virtually everything that mattered in black popular music

that came after it is beyond question – “Earth Song,” written and sung by the

lead singer on “Mama’s Pearl” a generation later, might as well have been

called “What About Marvin?” – but what about other significant records released

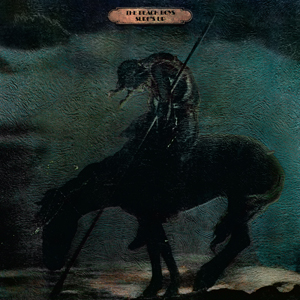

that year? One not particularly obvious contender springs to my mind; it

contemplates the world’s imminent ruination, wonders what the hell happened, to

the point where its lead song is entitled “Don’t Go Near The Water,” not to

mention the prominent use of flute on “Feel Flows”:

4.

Upon its release, What’s

Going On? was usually reviewed in tandem with Stevie Wonder’s Where I’m Coming From.

5.

Apropos moonshots, spiritual flutes, etc., Gil

Scott-Heron was active and recording by this stage.

6.

Returning to what is essentially a remix of the piece I

wrote about this record fifteen years ago – and you can’t really just write

about the title song alone – and therefore requiring to listen to the record

again, I was struck, and not in a good way, by how little, if at all, its

sentiments had dated. If anything it all now sounds far more horrifically

up-to-date than it did in 2003, in a world which appears intent on regressing

to the year 1003. It suggests that nothing has been learned, that the

rebuilding of society, advancement of humanity and preservation of the planet

matter less than the shrill transient needs of a fundamentally superstitious

species which has yet to evolve beyond a third-grade level of comprehension of

the world. I realise that this is premeditated and orchestrated by people who

fancy themselves to be in charge of things – because nobody has the courage to

challenge them – that we are now forever expected to satisfy the lowest common

denominator when we should be seeking to stimulate the highest. Or, in my case,

loud idiots determined to bring down and destroy every belief and value I was

brought up to respect. In this setting, What’s

Going On? stands as a siren to warn against the continuing downslide into

superstitious medieval peasantry.

Date Record Made

Number Two: 10 April 1971

Number Of Weeks At

Number Two: 3

Records At Number One:

“Just My Imagination (Running Away With Me)” by The Temptations and “Joy To The

World” by Three Dog Night

UK Chart Position: 80

(1983 reissue)

Comments

Post a Comment